Written by Laurian Douthett, former Archivist Assistant

Edited by Rona Razon and Beth Bayley

Thomas Whittemore in Kariye Camii, ca. late 1940s or early 1950. From the collection: Thomas Whittemore Papers, ca. 1875-1966. Image Collections and Fieldwork Archives.

Thomas Whittemore passed away over half a century ago, but traces of his presence can still be found in archival collections, articles, fictional books, and films. Whittemore led a sprawling sort of life – he was the kind of man who knew everyone and went everywhere. He was the companion of Russian princesses and Italian kings, American heiresses and French artists, and some of the poorest exiles and refugees anywhere. The other noteworthy thing about Whittemore is that people responded to his personality in a positive or negative way – that is, they either loved him or hated him. A small, energetic man, deeply religious and a vegetarian, he was given to pithy remarks and had a high regard for beauty. He used his charm and intelligence to convince his wealthy friends and acquaintances that being a patron of Byzantine art was a good and noble thing for them to do. In doing so, he brought the world of Byzantine art to a contemporary American audience, thus making the globe he so loved to travel a little bit smaller.

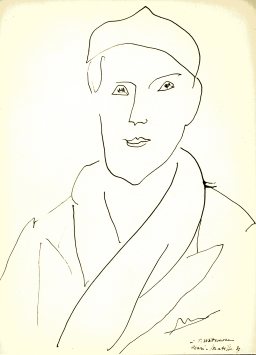

Drawing of Whittemore from his earlier years. From the collection: Thomas Whittemore Papers, ca. 1875-1966. Image Collections and Fieldwork Archives.

Over the past 2 years, the ICFA team has attempted to piece together bits of information on Whittemore’s life and work. It seemed at first that little remained of the character that put so much time and effort to the preservation and restoration of Byzantine art and architecture. Nevertheless, we have found records of his travel, which would sometimes cover several countries in a few months. We have descriptions and photographs of him in various costumes. We also have the records of his work life, and his own writing on both the mosaics of Hagia Sophia and on the humanitarian work he championed in Russia and Turkey. We even found fictionalized or lightly disguised versions of Whittemore in Edith Wharton’s 1922 novel Glimpses of the Moon, Graham Greene’s “Convoy to West Africa,” (The Mint, no. 1 1946), and Evelyn Waugh’s Remote People (1934). More importantly, he figures in archival collections at other institutions, such as Harvard University, the Archives of American Art of Smithsonian Institution, and the Byzantine Library at Collège de France.

Thomas Whittemore (T, T.W., Tom, Tommy, Thomas, Whittemore, Prof. Whittemore, or Dr. Whittemore) was born on January 2, 1871 in Cambridgeport, Massachusetts. In 1894, he received his Bachelor’s degree in English Literature from Tufts College, where he assumed teaching position shortly after graduation. A year later, he attended the Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, but never obtained a degree. Based on our research, Whittemore began to develop an interest in art history, particularly Byzantine studies, in early 1900s. He also traveled extensively in Europe, spending time in both France and Russia. He was quite enmeshed within the artist communities of Paris, and particularly interesting is a record of his friendship with prominent artists of the time, such as Henri Matisse and Gertrude Stein.

Sketch of Thomas Whittemore by Henri Matisse. From the collection: Thomas Whittemore Papers, ca. 1875-1966. Image Collections and Fieldwork Archives.

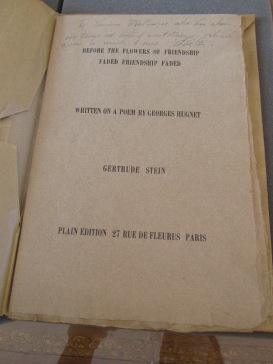

A book by Gertrude Stein, with a handwritten dedication to Thomas Whittemore by the author. Book available at: Dumbarton Oaks Rare Book Collection.

By 1916, Whittemore’s interests turned east, and his priorities shifted to the war efforts in Russia. After The Great War began, he became actively involved in the relief effort for the American Red Cross. He championed the cause for Russian relief and joined The Committee for the Relief of War Refugees. During this time, Whittemore was in and out of various countries to collect or deliver donations, from the United States to Japan and then back to Russia or Turkey. Whittemore took great pride in these initiatives and spoke of his difficult endeavors in letters to his friends, such as Isabella Stewart Gardner:

In the report you will know what I am doing. In the rest you will know what I am feeling. I see many Russians and try to reshape many lives and I am a good deal alone.

(Source: Isabella Stewart Gardner Papers, 1760-1956, microfilm copies are available at the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

Additionally, he helped promote education for exiled Russian youth and established relationships within the refugee circle. This is important to note when it comes to understanding later events in Whittemore’s life, especially the formulation of the Byzantine Institute, as many Committee members and former refugees became involved with the Institute in the early 1930s.

Whittemore founded the Byzantine Institute in 1930 in order to study, conserve, and restore art and architecture in the former Byzantine Empire. He was joined by prominent individuals, such as Charles R. Morey, John Nicholas Brown, Charles R. Crane, George D. Pratt, and Matthew S. Prichard. The conservation and restoration work in Hagia Sophia, one of the major projects conducted by the Byzantine Institute, also prompted similar projects in Turkey in the 1940s (e.g., Kariye Camii). Supposedly, the project in Hagia Sophia became possible after a meeting between Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and Whittemore, an event that has been sparsely documented. This prompted the uncovering of mosaics that had for the most part been covered from the time of the conquest of Constantinople in 1453. Furthermore, according to correspondence and scholarship, a meeting between the two may have led not only to the conservation and restoration of Hagia Sophia, but also to the conversion of the mosque to a secular museum.

While unrelated to this thinly documented meeting, a photograph from a yellowing newspaper clipping found in the collection illustrates Whittemore’s relationship with Atatürk. Although we could not determine the origin or source of the newspaper, Günder Varinlioğlu, ICFA’s former Byzantine Assistant Curator, suggests that this photo may have been an official photograph of the two individuals that was distributed to local newspapers in Turkey.

Photo of Thomas Whittemore with Mustafa Kemal Pasha Atatürk from a newspaper clipping. From the collection: The Byzantine Institute and Dumbarton Oaks Fieldwork Records and Papers, ca. late 1920s-2000s. Image Collections and Fieldwork Archives.

Whittemore devoted the next two decades of his life to the Byzantine Institute and to the preservation of Byzantine art and architecture. He carried out the negotiations with government officials in Turkey, obtained work permits, recruited skilled fieldworkers, organized fundraising events, managed the Byzantine Institute staff, and delivered fieldwork supplies to and from the various sites. He spent roughly half the year fundraising among his wealthy friends and the other half overseeing fieldwork at Hagia Sophia – usually passing through Paris and the Byzantine Library along the way.

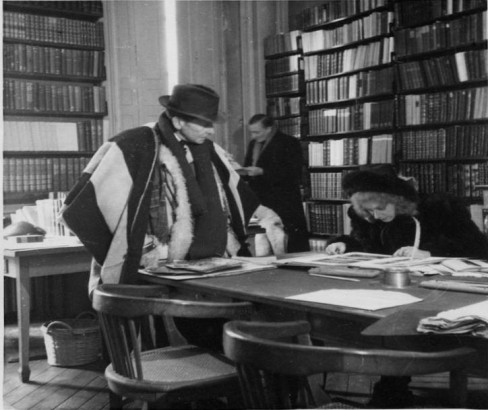

Thomas Whittemore, flamboyantly garbed in thick shawls and scarves, possibly observing a researcher or an Institute staff member at the Byzantine Institute Library in Paris. From the collection: Thomas Whittemore Papers, ca. 1875-1966. Image Collections and Fieldwork Archives.

On June 8, 1950, as he was about to enter the conference room in the office of John Foster Dulles at the State Department in Washington, D.C., Whittemore suffered a heart attack and died at the age of 79. He is buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, MA.

Whittemore family plot, Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Photograph taken by former ICFA intern, Caitlin Ballotta (Harvard ’14)

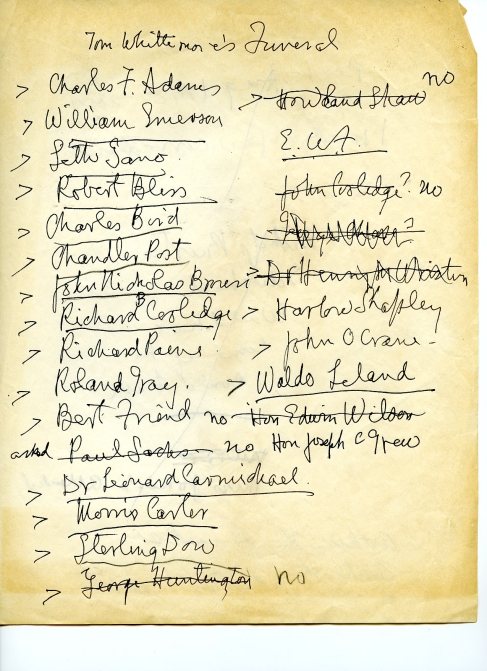

List of people invited to Whittemore’s funeral. From the collection: Thomas Whittemore Papers, ca. 1875-1966. Image Collections and Fieldwork Archives.

Pingback: Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Institute – Moving Image Collection | archaeoinaction.info

Pingback: The Byzantine Institute Fieldwork Notebooks | icfa

Pingback: “Earthquakes and war they have survived…” | icfa

As his only decendant, (while as a collateral line – his brother John St. Clair W. was my great grandfather) I can add a few interesting things – first he was christened Benjamin Franklin W. as testafied by the family bible, (which I ave) and he changed his name to Thomas when he was 4 years of age!! As written by his mother. I also have a silver baby cup which was also in his estate that my mother bought. A Russian samovar with the royal stamps on the front; an Egyptian grave figure ( 1 1/2″;, a Chinese grave figure, Tang dynasty, certified by Oxford University;, a carved ivory deer, I believe is African. A copy of the charcoal drawing by John Singer Sargeant the original in the Gardner Museum. IS THERE ANY WAY THAT I AND SOME OF MY FAMILY COULD HAVE AN APPOINTMENT TO SEE YOUR COLLECTIONS? My middlename is Whittemore and he was my godfather! I live in Potomac, Md. so it would be easy for us to go.

To request access to the archives, please see the form here: http://www.doaks.org/research/library-archives/access-and-hours/request-access

Pingback: Hagia Sophia Homecoming: Returning to Istanbul after World War II | icfa

Pingback: Hagia Sophia Homecoming: Returning to Istanbul after World War II - Israel Foreign Affairs News

Pingback: Kâmâl’in ve inönü’nün batı sevgileri – Can Ahmed köse