Written by Jan Zastrow, ICFA volunteer and Certified Archivist

The project to conduct a Census of Byzantine and Early Christian Objects in North American Collections began 75 years ago in late 1938 by Mrs. Mildred Bliss, co-founder of Dumbarton Oaks. It was a way to document, catalog, and depict the treasures of Byzantium in museums and private collections all over North America for research access in one place here in Dumbarton Oaks, similar to Princeton’s Index of Christian Art. And in the uncertain times before World War II, it was also a way to obtain detailed information and photographic surrogates for these objects, in the eventuality of damage or destruction if war broke out on this side of the Atlantic.

The Census changed names over the course of time as its scope was developed and refined. In one of the earliest references in late 1939, it was called the “Census of Early Christian, Byzantine and related arts in the United States and Canada” (in Elizabeth Dow’s report of the Forty-First General Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 44, No. 1, p. 115). In the 1941-1942 Dumbarton Oaks Annual Report (p. 5), it was called the “Census of Late Antique and Early Mediaeval Objects in American Collections,” but was later referred to as the “Census of Objects of Early Christian and Byzantine Art in the United States and Canada,” or alternatively the “Census of Byzantine and Early Christian Objects in North American Collections.” Likely the term Byzantine was added to emphasize the eastern Mediterranean focus. After that it was simply called the “Byzantine Object Census” for short.

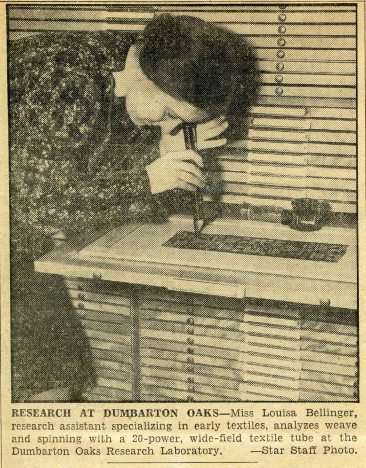

The Census project was administered by Elizabeth Dow (later Elizabeth Dow Pritchett) from 1938 to 1943, with the assistance of textile specialist Louisa Bellinger from 1939 to 1942. Work resumed in the mid-1950s through 1966; the Census was added to as late as the mid-1980s. Textiles were but one subset of the Byzantine Object Census, which included many types of media: bronze, ceramics, glass, metalwork, leather, mosaic, wood, etc. Bellinger was the expert textile analyst, while Dow Pritchett handled all the other formats and served as overall project manager.

Louisa Bellinger, September 1940

Bellinger also wrote and edited an inhouse newsletter at Dumbarton Oaks, The Underworld Courier, for the duration of its existence from January to October 1941. These “editions” were actually typed letters with photographs, musical programs, stories, drawings, and notes tipped in so as to keep Mr. and Mrs. Bliss up to date on Dumbarton Oaks happenings while Mr. Bliss was convalescing in California from an illness. Any serious textile student would want to read these for Bellinger’s detailed fiber notes. The photo below of Bellinger examining weave and spinning with a textile tube came from a February 9, 1941, Sunday Star newspaper clipping, attached to the February 15, 1941, edition of the Underworld Courier (v. 1, no. 6, p. 7).

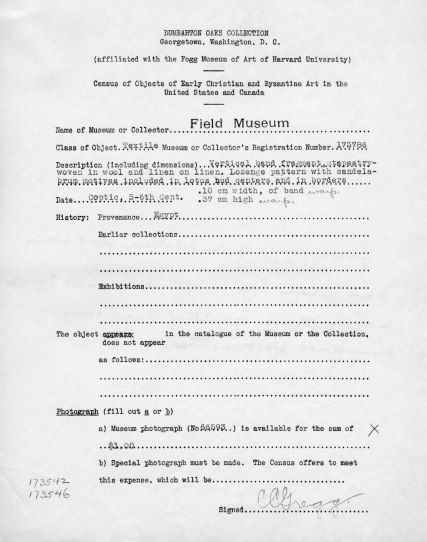

As far as we can tell, the Byzantine Object Census project seemed to work like this: an introductory letter and blank survey forms (“object reports,” see sample below) were sent to institutions and private collectors in North America known to hold articles of Early Christian and Byzantine art. Then, participating institutions filled out the object reports and mailed them back to Dumbarton Oaks. Project staff sifted through the forms, made selections, and ordered photographs of specific works to be included in the pictorial Census. These prints would be mailed to Dumbarton Oaks where they would be processed: mounted on board, assigned an accession number, and then a catalog card linking the description to the photograph of the object would be created—an analog precursor to the relational database!

Object Report from the Field Museum in Chicago

In the early years of the Census, between 1939 and 1942, Dow and Bellinger frequently traveled to museums with numerically large or incompletely cataloged Byzantine collections to examine the registrars’ records, identify uncataloged items, and make their selections in person. Bellinger actually spent several months in late 1940 at the Field Museum in Chicago, documenting and analyzing textiles there. One issue of the Underground Courier goes into marvelous detail about working with the textiles in the rarefied Mummy Case and the astonishment of schoolchildren watching her work through a small window inside that “sealed” chamber (Administrative Papers, Louisa Bellinger, Underworld Courier, v. 1, no. 4, p. 2.)

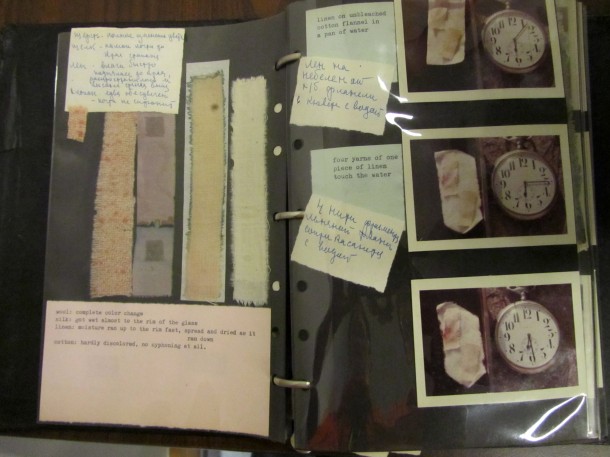

Bellinger conducted scholarly research in the form of onsite examinations and technical experiments to document the creation, purpose, and history of textile works for various Byzantine, Coptic, and Middle Eastern collections throughout the United States and Canada. The objective of Bellinger’s experiments was to determine the creation processes of specific textile fabrics by studying their individual components, such as linen, flax, or wool. After the fibers used in a textile work were identified, Bellinger would conduct further experiments involving environmental and chemical changes to test the durability of specific types of fabrics. Bellinger’s experiments are documented in photographs, negatives, slides, and films. Her scrapbook, pictured below, contains timed photos of experiments with actual scraps of fiber, wood … and copious notes.

Louisa Bellinger’s Textile Experiments Scrapbook

Although the Textile Census was apparently never supplemented after Bellinger left Dumbarton Oaks in 1942, the Object Census was resumed by Ms. Fanny Bonajuto from 1956 until 1966 and continued to be updated by Library staff through the mid-1980s. As of 2013—the 75th anniversary of the start of the Census—some pieces of the puzzle are still missing: painstakingly crafted accession numbers on negatives have no corresponding inventory lists or descriptions, some object reports have no photographs, and some photographs have no object reports. Bits and pieces have been found all over the repository and reunited, but it remains a mystery why such a useful tool was allowed to fall into disuse. Now it’s our job to “put Humpty Dumpty back together again.” Research in the collection is welcomed, although be warned: we might put you to work solving a few outstanding mysteries!

References:

“Forty-First General Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America,” American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 44, No. 1, pp.105-116.

The Bulletin of the Fogg Museum of Art, “A Special Number Devoted to the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection,” Volume IX, 4 (March 1941), pp. 67-68.

Dumbarton Oaks Archives, Administrative Papers, Louisa Bellinger, Underworld Courier.